A Shot in the Dark (1964 film)

| A Shot in the Dark | |

|---|---|

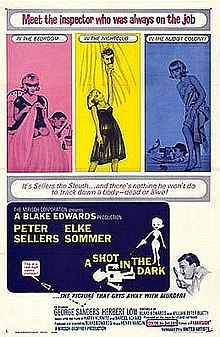

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Blake Edwards |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on |

|

| Produced by | Blake Edwards |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Christopher Challis |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Henry Mancini |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 102 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Box office | $12.3 million[2] |

A Shot in the Dark is a 1964 comedy film directed by Blake Edwards in Panavision. Produced as a standalone sequel to The Pink Panther, it is the second installment in the eponymous film series, with Peter Sellers reprising his role as Inspector Jacques Clouseau of the French Sûreté.

Clouseau's blundering personality is unchanged, but it was in this film that Sellers began to give him the idiosyncratically exaggerated French accent that was to later become a hallmark of the character. The film also marks the first appearances of Herbert Lom as his long-suffering boss, Commissioner Dreyfus, as well as André Maranne as Dreyfus's assistant François and Burt Kwouk as Clouseau's stalwart manservant Cato, all three of whom would become series regulars. Elke Sommer portrays the murder suspect, Maria Gambrelli. The character of Gambrelli would return in Son of the Pink Panther (1993), this time played by Claudia Cardinale, who appeared as Princess Dala in The Pink Panther (1963). Graham Stark, who portrays police officer Hercule Lajoy, would reprise this role eighteen years later, in Trail of the Pink Panther (1982).

The film was not originally written to include Clouseau, but was an adaptation of a stage play by Harry Kurnitz, which he adapted from a French play L'Idiote by Marcel Achard.[3] The film was released only a year after the first Clouseau film, The Pink Panther. It is the first film in the series in which Clouseau could be considered a main character.

Plot

[edit]Late at night at the country home of millionaire Benjamin Ballon, several of its occupants are moving about rooms, hiding and spying on others. The household consists of: Ballon's wife Dominique; Henri LaFarge, the head butler, and his wife Madame LaFarge, the cook; Miguel Ostos, the head chauffeur; Pierre, the second chauffeur, and his wife Dudu, the head maid; Georges the gardener, and his wife Simone, the second maid; Maria Gambrelli, the third maid; and Maurice, the second butler. The night's events soon end with gunshots in the room of Maria, with Miguel found murdered.

Inspector Clouseau of the Sûreté, a blundering and inept detective, arrives on the scene, accompanied by his assistant, Hercule Lajoy. Suspicion is cast upon Maria, as she was found by Maurice clutching the gun that killed the victim. Before Clouseau can investigate further, his superior Commissioner Dreyfus removes him from the investigation out of fear he will bungle a high-profile case.

The following day, while training with his manservant Cato under a strict unplanned arrangement between them, Clouseau is reinstated to head the investigation after Dreyfus is ordered by his superiors to do so, through Ballon's political influence. In discussion with his assistant, Hercule about the murder, Clouseau asserts that Maria is innocent despite the evidence against her, but believes she is protecting the real killer who he suspects might be Ballon himself. To keep her under surveillance during the investigation he arranges for her release from prison. However, two more murders occur—Georges in the Ballons' greenhouse; and Dudu at a nudist camp—with the evidence pointing towards Maria in each case. Despite the facts, Clouseau continues to believe she is innocent, which leaves Dreyfus dismayed at his incompetence in the case and the scandals he causes. After the body of Henri is found in the closet of Maria's bedroom, Clouseau is again removed from the case.

Although Dreyfus begins to suspect Ballon is attempting to hide facts about the murders, assuming that he is shielding someone with Maria's help, Clouseau's theory about her innocence leaves Dreyfus worried that he could be undone. When Dreyfus is again forced to put Clouseau back on the case, he eventually suffers a nervous breakdown upon hearing of Clouseau going out for the evening with Maria. That night, several attempts are made on Clouseau's life by a stalker at various establishments, including his apartment, but all of these fail while resulting in the deaths of several innocent bystanders. The increased notoriety of the case as a result of the incidents, coupled with proving Clouseau's theory correct, slowly cause Dreyfus to become unhinged.

Clouseau finally decides to confront the entire Ballon household over the murders, hoping to trick the murderer into revealing himself. However, his plan unexpectedly proves Maria innocent in all four murders. Dominique reveals she killed Miguel by mistake, believing he was her husband who she thought was having an affair with Maria; Madame LaFarge murdered Georges, with whom she was having an affair, because he was about to leave her for Dominique; Simone killed Dudu in order to maintain her affair with Pierre; and Ballon murdered Henri because he was having an affair with Dominique. Pierre also reveals that Maurice was blackmailing Ballon. Meanwhile, Dreyfus is revealed to be the stalker targeting Clouseau previously. Dreyfus plants a bomb in Clouseau's car in one more attempt to kill him. Clouseau's plan comes to its climax when Hercule cuts the house lights in the midst of the chaos. The Ballons, Madame LaFarge, Pierre, Simone, and Maurice flee and attempt to escape in Clouseau's car, unaware of the bomb, and the car explodes as they drive off. Believing everyone was innocent, despite what they had confessed to, Dreyfus loses his sanity and is dragged away by Hercule. Clouseau, embracing Maria, finally declares her innocent, but a passionate kiss between them is swiftly interrupted when Cato makes a sneak attack.

Cast

[edit]- Peter Sellers as Inspector Jacques Clouseau

- Elke Sommer as Maria Gambrelli

- Herbert Lom as Commissioner Charles Dreyfus

- George Sanders as Monsieur Benjamin Ballon

- Graham Stark as Hercule Lajoy

- André Maranne as Sgt. François Chevalier

- Martin Benson as Maurice

- Burt Kwouk as Cato[a]

- Tracy Reed as Dominique Ballon

- Moira Redmond as Simone

- Vanda Godsell as Madame LaFarge

- Maurice Kaufmann as Pierre

- Ann Lynn as Dudu

- David Lodge as Georges

- Douglas Wilmer as Henri LaFarge

- Reginald Beckwith as Receptionist

- Bryan Forbes as Turk, the Nudist Camp Attendant[b]

- André Charrise as Game Warden[c]

- Howard Greene as Gendarme

- John Herrington as The Doctor

- Jack Melford as The Psycho-Analyst

- Victor Baring as Taxi Driver

- Victor Beaumont as Gendarme

- Tutte Lemkow as Cossack Dancer[d]

- Hurtado De Cordoba Ballet as Flamenco Dancers & Guitarist

- Fred Hugh as Balding Customer

- Rose Hill as Soprano

- Tahitian Dance Group as themselves

Production

[edit]Sellers was attached to star in the adaptation of Harry Kurnitz's Broadway hit before the release and success of The Pink Panther, but was not pleased with the script by Alec Coppel and Norman Krasna. Walter Mirisch approached Blake Edwards and asked him to take over as director of A Shot in the Dark from Anatole Litvak. Edwards declined initially, but eventually relented under pressure on the condition he could rewrite the script, substitute Inspector Clouseau for the lead character, and choreograph comic scenes on the fly as he and Sellers had successfully done for their previous film.[4]

Edwards' rewritten script bore little resemblance to Kurnitz's play, and in response Sellers's co-star Walter Matthau quit the film. Sophia Loren also had to quit several days before production began to recover from throat surgery. After Shirley MacLaine turned down the role, Romy Schneider was cast. However, she also had to quit due to her commitments with Good Neighbor Sam (1964) and was replaced with Elke Sommer. Sommer used part of her salary to "buy her way out" of a film deal in West Germany and sign a new contract with MGM Studios.[5]

Principal photography began on November 18, 1963, at MGM-British Studios in Borehamwood, England. Shooting also took place in Paris and London.[5] The relationship between Edwards and Sellers deteriorated to such a point that at the conclusion of the film they vowed never to work together again. They eventually reconciled to collaborate successfully four years later on The Party, and on three more "Pink Panther" films in the 1970s.

Taking inspiration from his teacher Ed Parker in martial arts, Edwards created the new character Cato Fong using the American Kenpo style. Parker briefly worked alongside Edwards learning more about cinematography and suggested that he implement slow motions at certain fight scenes in order to increase the dramatic effect and make the moves more noticeable for audiences. Following a favorable response from viewers, Edwards continued to use this effect in following Pink Panther films.[6]

As with most of the other Clouseau films, A Shot in the Dark features an animated opening titles sequence produced by DePatie-Freleng Enterprises utilizing an animated version of Inspector Clouseau. This film and Inspector Clouseau are the only Clouseau films not to feature the Pink Panther character in the opening titles. Henry Mancini's theme for this film serves as opening theme and incidental music in The Inspector cartoon shorts made by DePatie-Freleng from 1965 to 1969. The title song, "The Shadows of Paris", was written by Henry Mancini. The singer is not credited but contemporary trade reports confirm it was Decca Records recording artist Gina Carroll.[7]

Reception

[edit]Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote, "It is mad, but the wonderful dexterity and the air of perpetually buttressed dignity with which Mr. Sellers plays his role make what could quickly be monotonous enjoyable to the end."[8] Variety wrote: "Wisdom remains to be seen of projecting a second appearance of the hilariously inept detective so soon after the still-current firstrun showing of 'Panther,' since some of the spontaneous novelty may have worn off, but the laughs are still there abundantly through imaginative bits of business and a few strike belly proportions."[9] Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times wrote that the film "is all variations of falling down and going boom ... I won't say 'ad nauseum' [sic] because Sellers is a clever comedian and never that painful to take. But enough is enough already."[10] Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post called it "a hardworking comedy," adding "While the lines are bright and sometimes blue, the real fun comes from sight gags, an old if neglected film ingredient."[11]

The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote, "Where The Pink Panther had style and a certain subtlety, its successor ... can substitute only slapstick of the crudest kind. As the bumbling inspector, Sellers is this time absolutely out of hand, his principal—and endlessly repeated—gag being to fall with a resounding splash into large quantities of water."[12] John McCarten of The New Yorker wrote, "'A Shot in the Dark' as done on Broadway was a mediocre comedy, but Blake Edwards, who directed the film and collaborated on the script with William Peter Blatty, had the good sense to toss the foundation stock out the window and let Mr. Sellers run amok ... All in all, extremely jolly."[13] The movie was one of the 13 most popular films in the UK in 1965.[14]

The film was well received by critics. It has 94% favourable reviews on review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes out of 32 reviews counted. The average rating given by critics is 8.1 out of 10. The critical consensus reads: "A Shot in the Dark is often regarded as the best of the Pink Panther sequels, and Peter Sellers gives a top-notch performance that makes slapstick buffoonery memorable."[15] In 2006, the film was voted the 38th greatest comedy film of all time in Channel 4's 50 Greatest Comedy Films. The film is recognized by the American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2000: AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs – #48[16]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10:

- Nominated Mystery Film[17]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "A Shot in the Dark (advert)". Evening Standard. 27 January 1965. p. 15.

- ^ Box Office Information for A Shot in the Dark. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ A Shot in the Dark by Marcel Achard and adapted by Harry Kurnitz had a 1961-1962 Broadway run, directed by Harold Clurman. Its cast included Julie Harris, Walter Matthau, and William Shatner.

- ^ Blake Edwards DVD director's commentary, The Pink Panther (1964), MGM Movie Legends DVD release 2007

- ^ a b "A Shot in the Dark". AFI Catalog. Retrieved 2024-11-12.

- ^ "Blake Edwards and the Martial Arts". Black Belt. No. 13. Patrick Sternkopf. June 1990. p. 10.

- ^ Gina Carroll - Bye Bye Big Boy, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (June 24, 1964). "Screen: Re-enter Sellers, the Sleuth". The New York Times: 28.

- ^ "A Shot In The Dark". Variety: 6. June 24, 1964.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (July 16, 1964). "'Zulu' Carries On in 'Geste' Tradition". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 13.

- ^ Coe, Richard L. (July 31, 1964). "Peter Sellers Stars at Town". The Washington Post. p. D5.

- ^ "A Shot in the Dark". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 32 (373): 27. February 1965.

- ^ McCarten, John (July 4, 1964). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. pp. 58–59.

- ^ "Most Popular Film Star." Times [London, England] 31 Dec. 1965: 13. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 16 Sept. 2013.

- ^ "A Shot in the Dark". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved 2016-08-06.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

External links

[edit]- 1964 films

- 1960s crime comedy films

- 1960s comedy mystery films

- American crime comedy films

- American sequel films

- British comedy mystery films

- 1960s English-language films

- Films scored by Henry Mancini

- American films based on plays

- Films directed by Blake Edwards

- Films set in country houses

- Films set in France

- Films set in Paris

- The Pink Panther films

- 1960s police comedy films

- British serial killer films

- American serial killer films

- United Artists films

- Films based on multiple works

- 1960s serial killer films

- Films with screenplays by Blake Edwards

- Films with screenplays by William Peter Blatty

- 1964 comedy films

- 1960s parody films

- Films shot at MGM-British Studios

- American films with live action and animation

- 1960s American films

- 1960s British films

- English-language crime comedy films

- English-language comedy mystery films

- Films shot in Paris

- Films shot in London